Hoi An and tourism

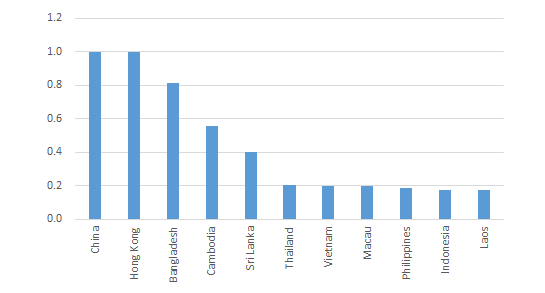

/TOURISTS TO HOI AN. SOURCE: HOI AN DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS

I’d have to say that Hoi An is my favorite city in Vietnam. The first time I was there was back in 2005, and it was just magical. I stayed at the Life Resort (which is now an Anantara). It was one of the few times in my life that I have run into anyone that I knew while abroad. It was my roommate for a summer in grad school - he was there at the same time with his wife. We had a wonderful time seeing the old city and eating and drinking.

Well, now the New York Times has written a “36 hours in…” column about Hoi An. That means it is over as an up-and-coming destination and is now a destination that has arrived. This may have been the case as far back as 1999, when UNESCO awarded the city World Heritage Site status.

We can see this in the tourist figures. Sadly, it is very difficult to get good figures, but based on older UNESCO reports (which have their own problems), and recent news reports, the number of visitors to the city has jumped. Back in 1999, there were about 150,000 tourists in Hoi An with about half Vietnamese. In 2005, when I visited, the numbers had risen to almost 650,000 (a 31% compound annual growth rate), but still a fairly equal mix of foreigners and nationals. Then in 2018, we saw another big jump. Total tourists were something like 3.3m in 2017, but in the first nine months of 2018, they had already reached 4.5m, with the international tourist figures alone (just for the first 9 months) was already ahead of the number for all tourist visits in 2017, almost a 20% growth rate.

So Hoi An is really seeing a massive onslaught of tourists. This in a city with just about 100,000 residents. The paradox of success for tourist destinations is that the more tourists come, the less magical it usually is. There are some exceptions: Paris, New York. But these smaller places, like Hoi An, are characterized by their quaintness and history. Having to shove some Western tourists with short shorts and a fanny pack aside to see the Japanese bridge, is less magical.

Having tourists, though, has its upsides. In a 2008 report, UNESCO reported some poverty data. The percentage of Hoi An households living with under VND260,000 (USD16.50) in income per month fell to 6.47%, compared to the national average of 14.7% for the nation as a whole. Data from a 2018 World Bank report shows the national poverty rate falling to 9.8%, with urban poverty down to 1.6%. Hoi An, although not explicitly mentioned, is classed in that urban poverty figure.

Hoi An needs to figure out a way to deal with the growth in tourists while also taking advantage of all the money coming in. If I were in charge, I would jack up the charge for people to visit the Old City (now about $6), try to upgrade the facilities to attract more well-heeled tourists, but also have a focus on cultural tourism (food, agriculture, religion, history). I think all of this would result in a more lucrative market but also one that hopefully preserves what I found most attractive about Hoi An when I visited 14 years ago.